Would we still have Agile today, if the Agile Manifesto had never happened?

What if the co-authors of the manifesto for agile software development had never come together in that 2001 Snowbird meeting or ever after? Would we still have something like Agile today?

What if the Agile avalanche was already set in motion many decades ago, in a disparate set of fields such as for example manufacturing, urban planning, architecture, international cooperation, …? What if the accelerating change and evolution of the world we live in have been the gravity and the inclined plane of an unavoidable Agile snowball?

Below you find a few anecdotes that seem to draw a trajectory inevitably leading to Agile Software Development. And the reason seems to be the nature, ubiquity and exponential progress of software and communications technologies and the related Cambrian explosion of (social, technical, financial) interconnections driven by the evolutions of the world we live in. The anecdotes below also reveal a broader perspective on Agility beyond software development. That perspective suggests sources and a repertoire of lessons that can be applied to Agile Software Development too.

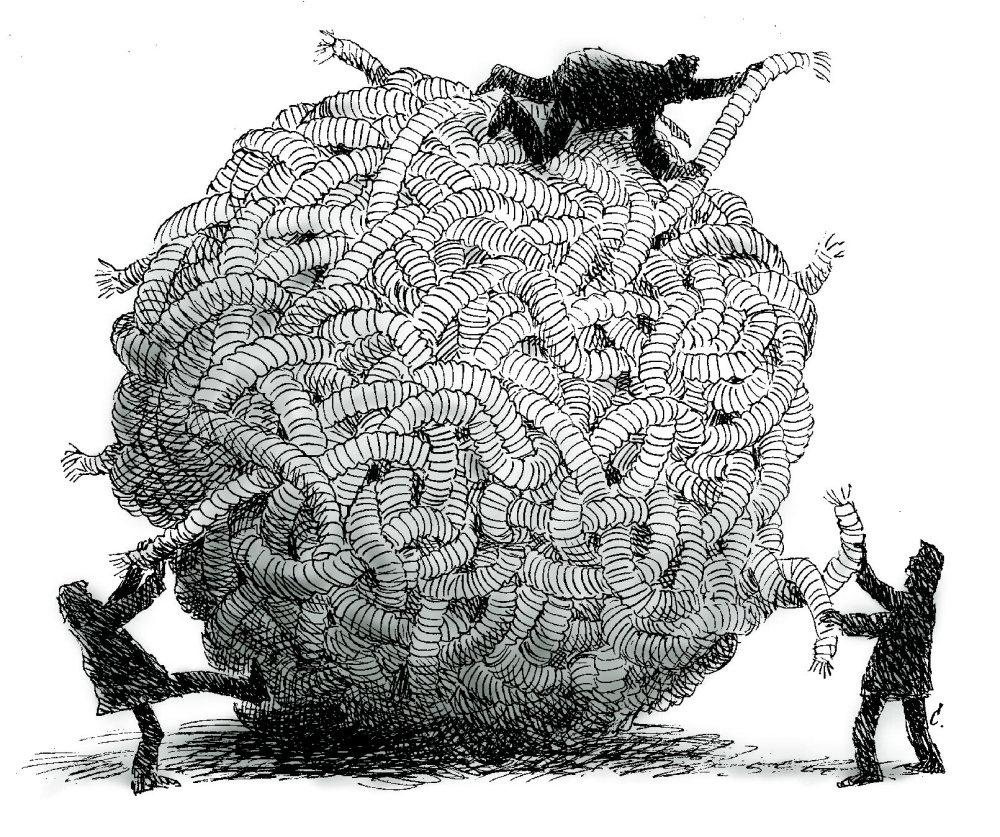

End of the 18th century, the Gordian knot

A Gordian knot is a metaphor and an early reference to intractable problems. In the 18th century intractable problems were of exceptional rarity.

1960s, the McNamara fallacy

Robert McNamara and the Whiz Kids had an astonishing rise to success after WWII thanks to the emergence of computers and operational research methods and their applications in mass-production manufacturing and well as in the US armed forces. They applied their expertise in using cutting edge technology and research to solve complicated problems (problems that require subject matter experts to identify the relevant best practice to solve the problem; they are quite different from Intractable problems tho’).

Thanks to this success McNamara become United States Secretary of Defence and later World Bank President. In these positions, he had to deal with intractable (AKA wicked, AKA complex) problems such as the Vietnam War and international cooperation.

He tried to solve these intractable problems using the same solutions that made him famously successful when he was dealing with complicated problems. As a consequence, he spectacularly and repeatedly failed, to the point that a fallacy was named after him, the McNamara fallacy. Quite an ironic paradox isn’t it?

Around the 60s those working in international cooperation and conflicts had to deal with intractable problems more than once in their lifetime if ever. Who else was facing intractable problems back then? Very few.

1960s and 1970s, Architecture and Urban Planning

Almost during the same time, after WWII, the industry and mass productions grow as did industrialised cities and their population. Approaches similar to those used by McNamara to solve complicated problems were used in urban planning.

In the 60s and 70s top-down and strictly quantitative methods were used in Urban Planning to plan for the use of the land, to design urban areas, to plan the consumption of natural resources, to design transportation and infrastructure, and to design spaces for the communities. The human factor, that may turn a complicated problem into a complex one, was ignored by the mainstream Urban Planning architects and intellectuals. Nowadays we know well that cities are complex, even more complex than the weather systems.

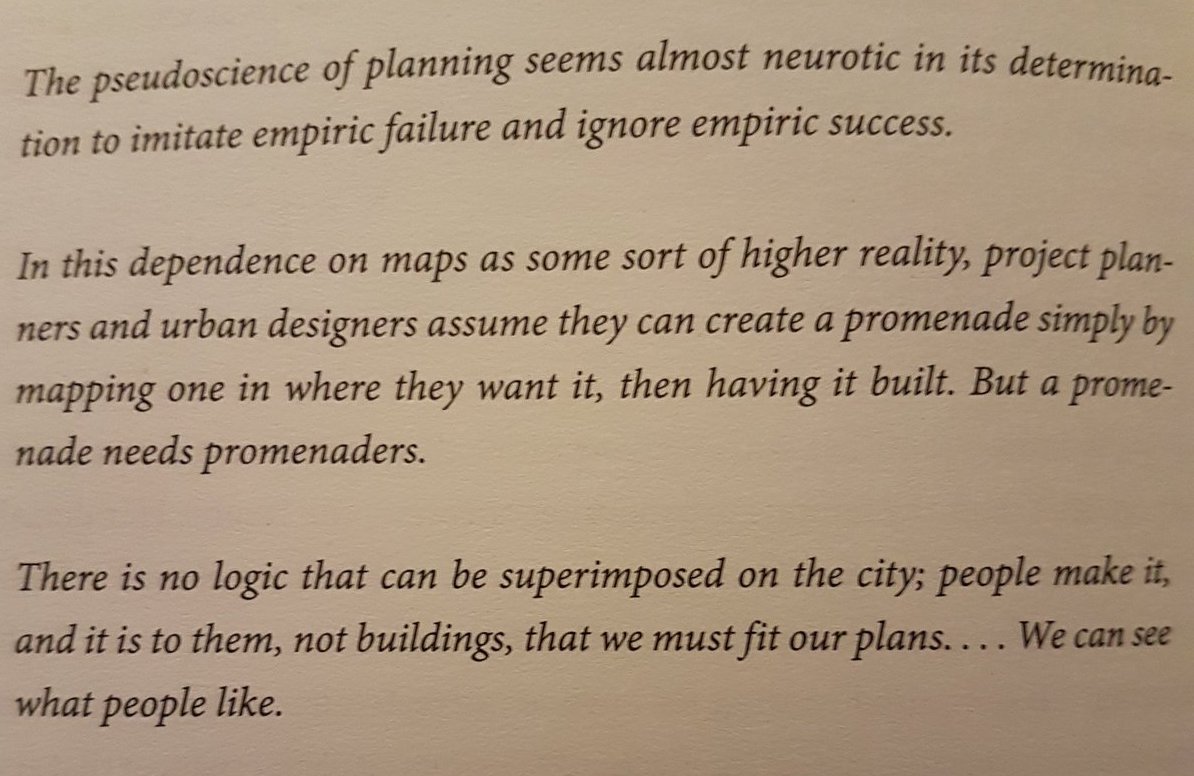

This mismatch between the complex nature of the problem and the approach for complicated problems being adopted, lead to repeated failures. Jane Jacobs, a journalist, author, and activist who influenced urban studies, sociology, and economics, in 1961 was one of the few to observe this mismatch and its consequences. This is an excerpt from Jane Jacobs:

In 1959 the Chicago Area Transportation Study describes the Desire path AKA Desire lines. It is a path created by human foot-fall traffic on the most easily navigated route, as opposed to promenades planned ignoring those they should serve.

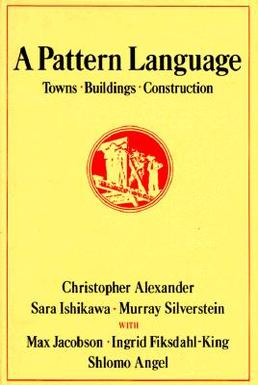

Christopher Alexander, architect and design theorist, like Jane Jacobs was one of the few to realise the impact of the human factor on the category of problems faced by architecture and design.

At the University of Oregon the protest of students against the process used to design their spaces led to the involvement of Christopher Alexander to design a different process by which the community of the university could create its own spaces (the human factor and the consequent complexity of the problem were in a way recognised). That work at the University of Oregon became the experimental testbed for material that later became the Christopher Alexander’s, bestselling book ‘A Pattern Language’.

His work on patterns influenced also software development, leading to the book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented, the creation of the Wiki, and it also influenced agile software development.

In the 60s and 70s only a small group of people had to deal occasionally with such complex problems of urban planning. In that group of people the majority ignored their systematic failures and the real nature of those problems. With the exceptions of Jane Jacobs and Christopher Alexander.

1967-1999, Science

During this period of time some scientists started to face some complex problems when studying economy, public health planning, weather forecast, environment, and politic. It was still a small group of people, and those problems were still uncommon.

In 1967 C. West Churchman mentioned, in a Management Science journal’s article, the term Wicked Problem to describe an intractable/complex problem that often eludes the solutions identified by Operational Research methods. In 1973 Rittel and Webber gave a formal definition of a Wicked Problem from their studies in social policy planning.

In 1985 Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus introduced the definition of a VUCA (as Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous) world (a world where complex problems are becoming common and frequent for a lot of people) when discussing leadership theories. Two years later, in 1987, the acronym was introduced. Also the U.S. Army War College used the term in relation to the multilateral world problems emerging at the end of the Cold War.

Ralph Douglas Stacey is an organizational theorist and Professor of Management. He noticed leaders, policymakers and managers facing complex problems in all organisations, where traditional planning and forecasting approach led to bad decisions and unintended consequences. So from 1991 he started to apply chaos theory and the models of complex adaptive systems (CAS) to organisations and management. This work led to the formulation of Stacey’s Matrix in 1996 to integrate mainstream management theories with the notion of organisations as complex adaptive systems.

During this time complex problems were gradually becoming more common for leaders of medium-large organisations. This was still a relatively small group of people. And such problems were not the norm yet.

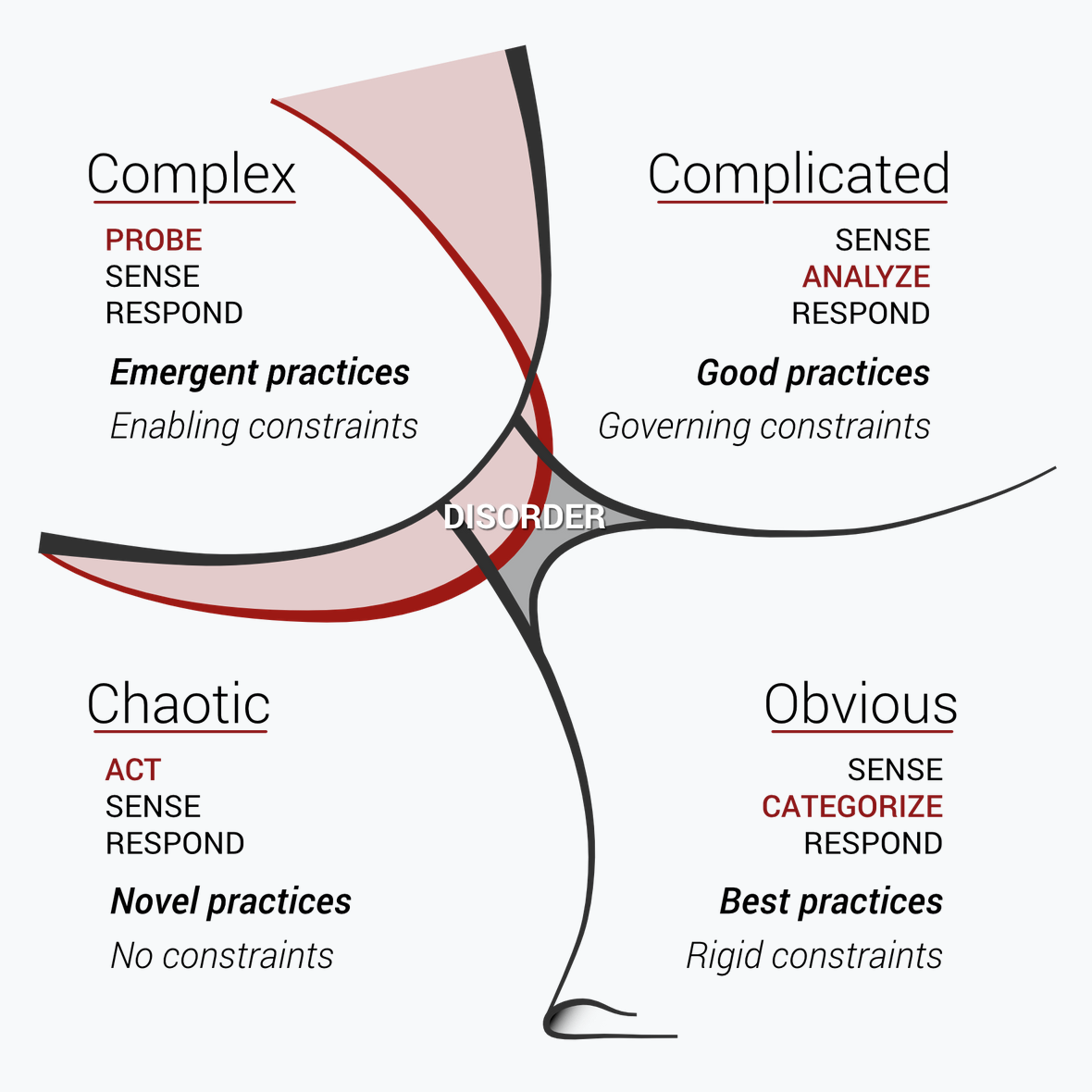

In 1999 David Snowden, a management consultant and researcher in the field of knowledge management, created the Cynefin framework (with contributions also from Cynthia Kurtz, Max Boisot and Alicia Juarrero) to support leaders in sense-making and decision-making when problems can have various characteristic including being complex. Cynefin framework contributed to formally define complex problems.

~2000-2013, Science

Scientists are facing complex problems more often and the study of complex problems intensifies. In 2008 Stuart A. Kauffman (theoretical biologist and complex systems researcher) comments on the ontological limit to predictability:

“My claim is not simply that we lack sufficient knowledge or wisdom to predict the future evolution of the biosphere, economy, or human culture. It is that these things are inherently beyond prediction.”

Stuart A. Kauffman

He also points out that physicists too are in a quiet revolution and he mentions Nobel laureates Philip Warren Anderson, Robert B. Laughingstocks and Isan Newton Media Leo Kandoff that are questioning the adequacy of reductionism.

NATO too is increasingly facing similar challenges, complex problems, in its multi-national military operations. During 2003-2013 David S. Alberts studies Agility for the military.

Complex problems are starting to become common for everyone.

During this time the Internet brings to everyone and everyday life the globalisation of ideas, information, and communication. This in turns amplifies the already ongoing globalisation of goods, services, financial transactions, travel, and work outsourcing. This expanding network of connections, frequent interactions, and interdependencies create complex dynamics that gradually brings the reality of complex problems into everyone and everyday life.

The complex problems that were experienced by the leadership of large organisations are gradually becoming a reality for everyone working in every-day life and in every organisation, especially those technologically more advanced and more connected to the Internet and its technological eco-system.

Conclusions

The constant evolution of the world we live in has created a reality where complex problems are common, frequent, and experienced by everyone everywhere. Tech companies have been at the forefront of this revolution and as such were the most likely to tackle this problem first.

Evidence also shows that in a variety of disparate areas and fields, others were tackling similar problems too. So it is safe to say that if the Tech industry and the co-authors of the agile manifesto would have not created agile, someone else would have developed an equivalent solution because it was valuable and necessary to do so.

Lucky enough the co-authors of the agile manifesto created agile and they did a great job. The inevitability does not make it less valuable, important or useful:

– that “whole” they created (bringing the lightweight methods together and give them a home) is *much much* more than the sum of its parts

– the connections of ideas and people (the agile alliance and the agile community) were instrumental in provoking the irreversible phase change that turned that underground minority movement into the new mainstream we have today.

The list of anecdotes above also suggests many fields and sources in addition to those traditionally referenced in agile software development with valuable learnings that can be reused and applied in software development too. See also: A collection of principles, theories and models relevant to Agile.

Boost your Agile to a whole new level of mastery.

See how we can help.

You, your team, your organisation.