Transcending Agile cross-team collaboration with Shared work (3-part)

Is there a valid alternative to Agile cross-team collaboration, one of the most consequential topics for successfully adopting Agile beyond one team? Should we tackle Agile cross-team collaboration challenges or transcend them?

PART TWO

The How-Tos of Shared work

Let’s have a look at some of the practicalities and options for this approach on how to

1) plan the work,

2) consider temporary cross-teams mutual support,

3) coordinate the work,

4) sequence the work,

0) retrospecting the collaboration

1) Planning the work

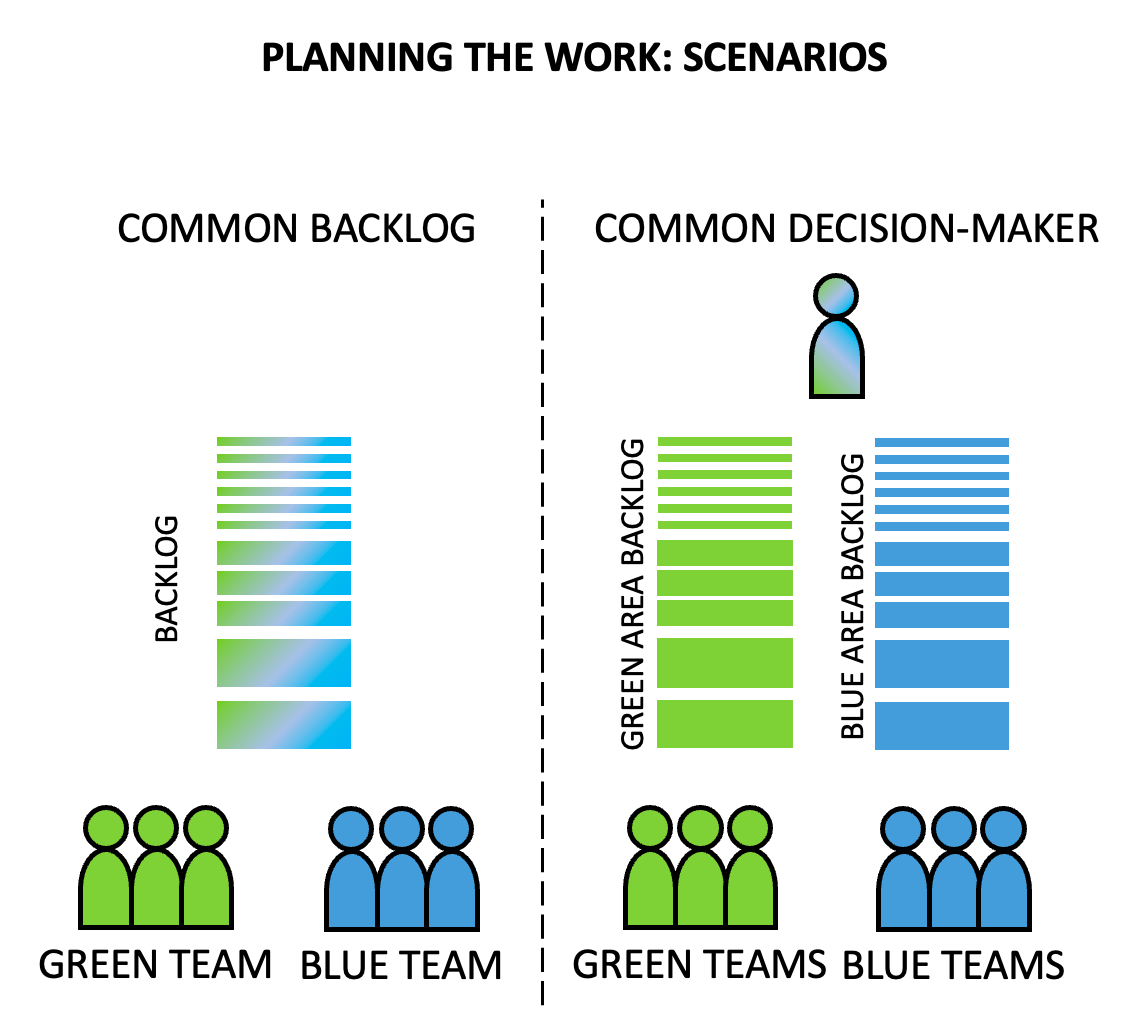

The most common scenario with shared work is to have teams working from the same common product backlog. When the number of teams grows closer to ten, the backlog is partitioned into distinct scope areas (AKA product area) each with a group of about 4÷10 teams.

- When the teams are from the same product or product area (share the same Backlog and the same priorities)

The product Backlog defines the plan and priorities for all the teams. So no additional planning effort is required other than allowing space for the teams to support each other as they see fit. XP does it with the Slack practice, adding a buffer in the plan in the form of some work that, if needed, can be dropped.

During the gradual refinement of the scope, including the high-level technical explorations, some knowledge sharing across teams may be necessary, so it must be allowed. For example, synchronising the teams’ refinement events and making them in physically/virtually neighbouring rooms. - When the teams work on the same product but in different areas of the product (have different Backlogs and priorities, but a common goal and a common decision maker)

Teams from different product areas can work independently and autonomously thanks to the shared product code ownership. A common decision maker, like an overall Product Owner, may help with decisions related to cross-product-area trade-offs. In the less frequent occasions when teams need to help each other, the teams and their Product area POs and stakeholders may need to harmonise their priorities. They may need to work together to fill skills and knowledge gaps by making the necessary learning happen.

2) Consider temporary cross-teams mutual-support

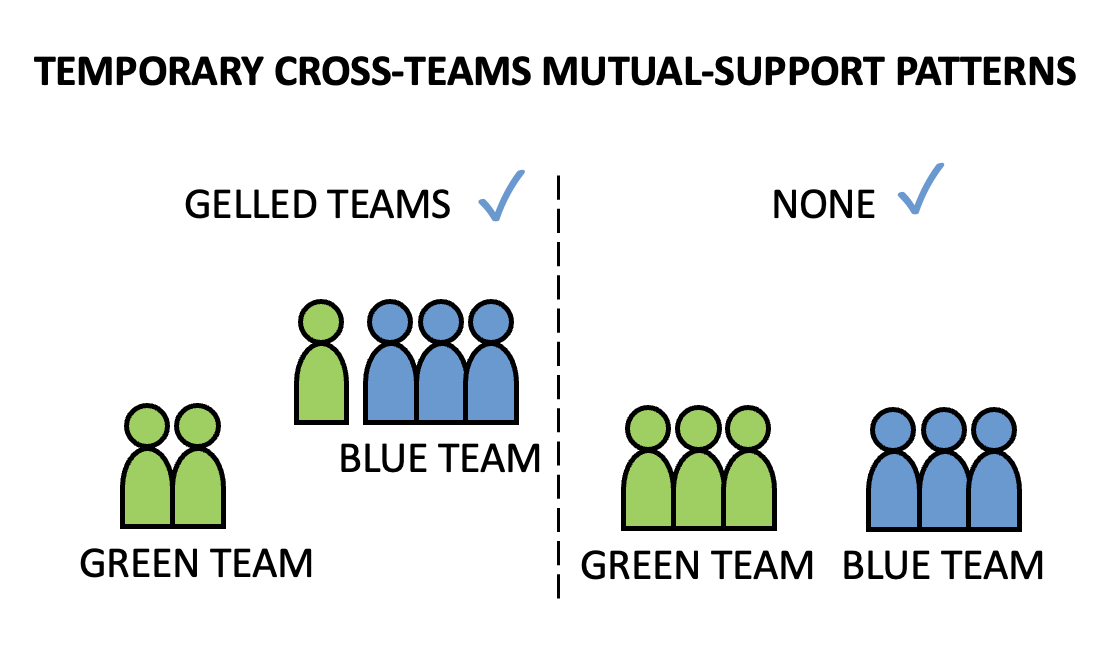

The two options discussed here last for the relatively short time needed to complete the work (a Backlog item, a User Story). And their goal is to allow a team to learn from another team to fill a gap and become able to complete an end-to-end customer-centric feature autonomously.

- Gelled teams helping each other

To share knowledge, mentor, and help each other as needed, relevant team members from a donor team, called travellers, join the recipient team. Both teams need to be stable long enough (18+ months) to avoid any damages from these temporary changes. Teams shouldn’t be suffering from knowledge silos either (e.g. they are practising pairing or mobbing/ensemble preventing knowledge silos). - None

It is the most common scenario. It occurs when the team can complete end-to-end customer-centric features autonomously.

3) Coordinating the work

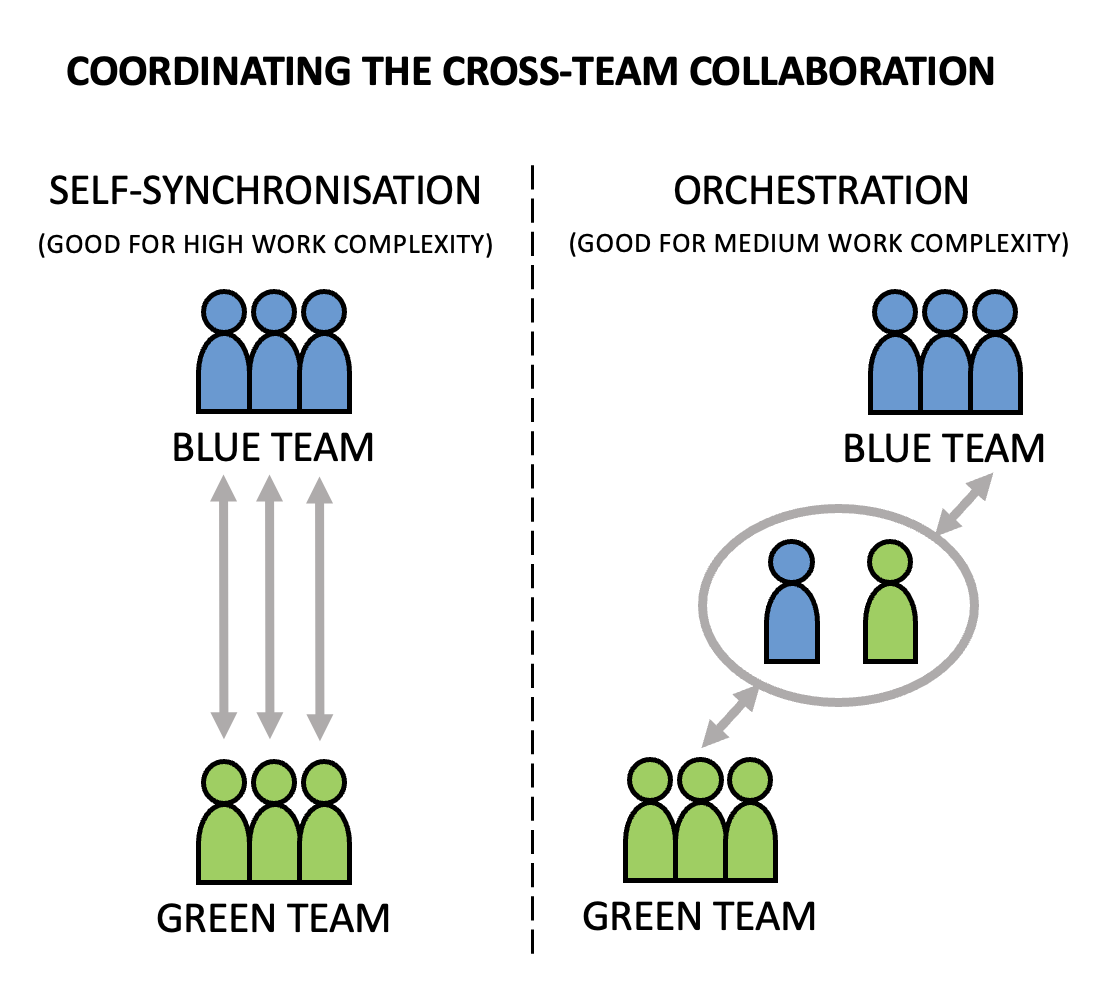

Since every team can complete end-to-end customer-centric features autonomously and there is shared product code ownership, the need for coordination is unusual. It occurs when learning across teams is needed to fill a knowledge or skill gap or where there is a massively large feature that, even after being split, requires multiple teams working closely together.

Below are two relevant approaches with a description of how they fit with the degree of Complexity of the work at hand (find more about the degree of Complexity in the book Living Complexity).

- Self-synchronisation

Self-synchronisation expects all the members of every team to be empowered to directly share information and coordinate their collaboration and work activities, as needed by the work at hand and its progress and evolutions. Imagine the players of a football team or doubles tennis players and how they work together.

In the previous point describing gelled teams mutually supporting each other, travellers visit another team to share knowledge and skills. A secondary effect of these travellers is the creation of an informal network of connections that can also serve as an open channel of communication to coordinate the work.

When the coordination is more intense and requires a more intentional and direct effort, each team can send out scouts to the other team(s) to work out the coordination. It can happen for the scope refinement, the planning, the high-level design, as well as while doing the work.

Since the teams are working on the shared product codebase, the loop of coordination can be closed on the tech side, ensuring additional speed and reliability by practising Continuous Integration, automated build and tests, and trunk-based development.

Work nature: This approach is a good fit for a type of work with a high degree of Complexity. Meaning it has a lot of uncertainties, unknowns, rapid changes and a high level of innovativeness. And as such, it requires a high bandwidth of information sharing and interaction and high-speed feedback loops. For the nature of the work, the collaboration protocol cannot be defined upfront and will emerge during the collaboration. It may remain fluid and continuously change until the completion of the work.

Team capability: It requires each team involved to be comfortable with this type of collaboration and have a good level of Agility. Below are two relevant approaches with a description of how they fit with the degree of Complexity of the work at hand (find more about the degree of Complexity in the book Living Complexity). - Orchestration

The need for orchestration is an exception since it is needed mainly for a massively large feature that, even after being split, requires multiple teams working closely together.

With orchestration, someone from each team, like the Scrum Master and the PO, is empowered to form a temporary orchestration workgroup lasting for a limited duration of the collaboration. The group shares relevant information and coordinates the collaboration and work activities across the teams.

This orchestration workgroup does not act as a (wo)man-in-the-middle. Instead, whenever direct collaboration between members of different teams is needed, they facilitate for it to happen and get out of the way.

When orchestration is to handle the collaboration due to a massively large feature, one of the teams involved may occasionally take the role of the leading team, facilitating the orchestration.

Work nature: This approach is a good fit for a type of work with some degree of Complexity. Meaning it has some uncertainties, unknowns, and some level of innovativeness. The orchestration facilitates the identification and definition of a collaboration protocol among teams that fits the work at hand: clear collaboration touch points (events) and interfaces (what is exchanged between teams, when, who, etc.)

4) Sequencing the work across teams

Since every team can complete end-to-end customer-centric features autonomously and there is a shared product code ownership, there is no need for sequencing the work across teams.

0) Retrospecting the collaboration

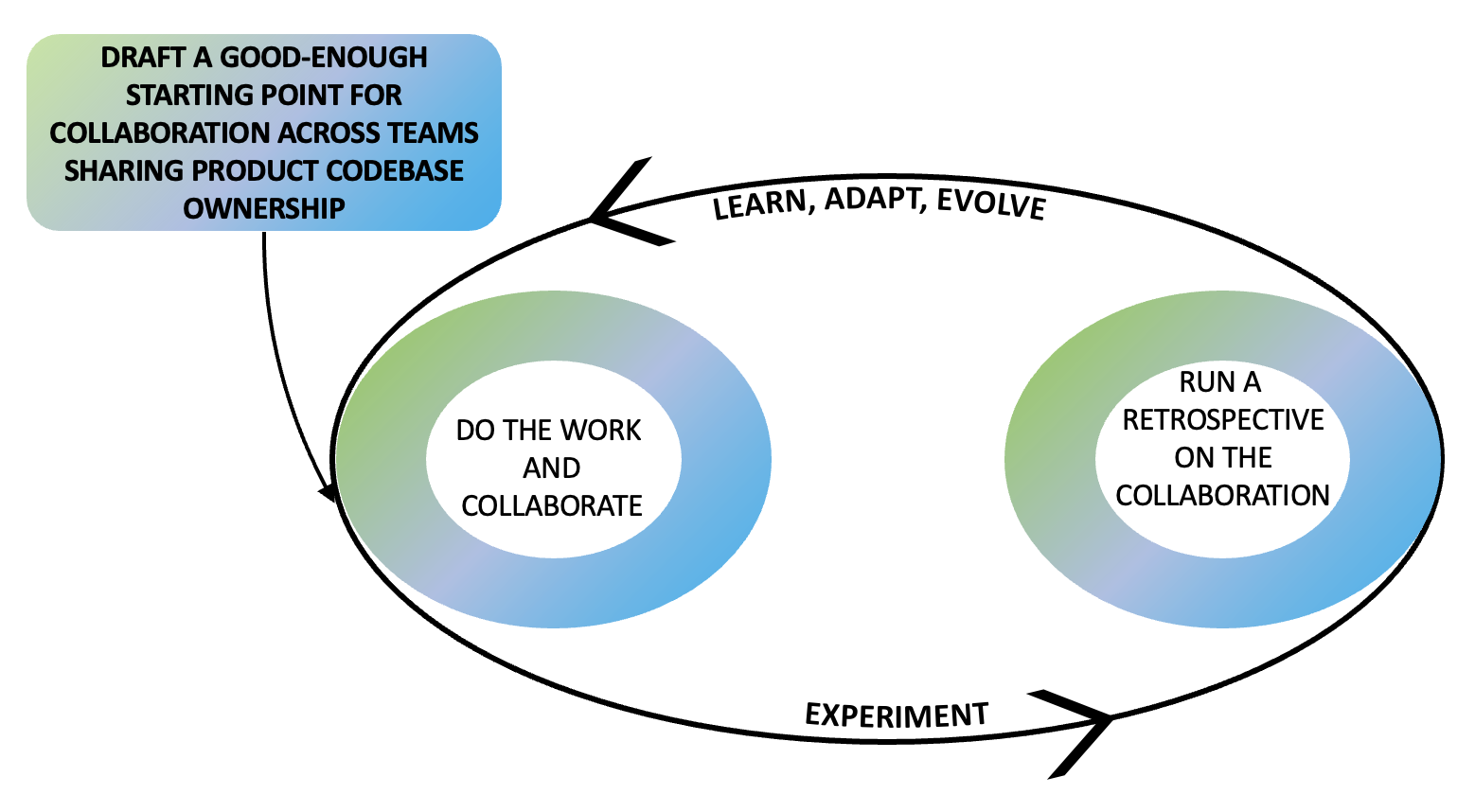

The teams that share product code ownership transcend cross-team dependencies and voluntarily collaborate to maintain and evolve the product and its codebase, share knowledge, learn new skills and mentor each other. It means the teams need some degree of consensus on technical practices and ways of helping each other. Several factors and combinations are at play that is impossible to find out upfront what will work well and what will not.

Therefore, to make it work in the given context and circumstances, it is better to begin from a simple starting point and experiment from there, learn, adapt and evolve along the way, with help from regular Retrospectives on all aspects of the collaboration across teams.

Organisational bottlenecks, obstacles and inefficiencies affecting the shared work and cross-team collaboration will emerge during the retrospective. It will lead to improvement actions on the governance, structure and composition of the teams, departments and the whole organisation.

Viktor Grgic pointed out the need for an organisational continuous improvement. This retrospective plays a big role driving the improvement toward the organisation’s specific needs and circumstances. It is an alternative to imitating canned solutions, standard solutions, or models copied from different organisations with different needs and circumstances.